Lessons From John McCarthy’s “Working the Wilderness”

“You can’t really trust someone who can lay their hands flat on a table, with no bent fingers or any bumps from calluses—they can only do paperwork, not the work out here.”

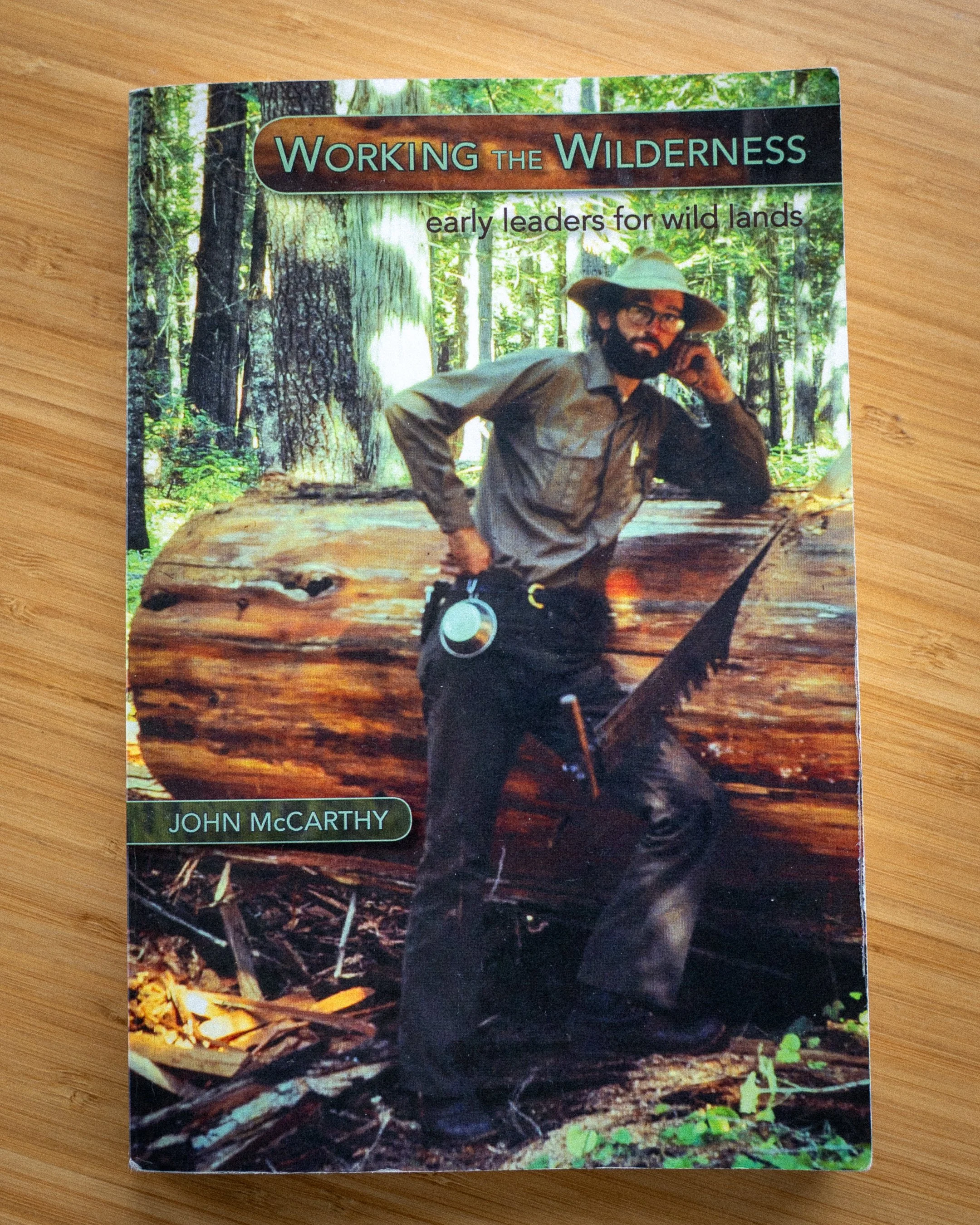

Those are the words of Emil Keck, the late, legendary ranger of Idaho’s Selway-Bitterroot National Forest. Emil is one of several colorful characters John McCarthy profiles in his 2019 book Working the Wilderness: Early Leaders for Wild Lands.

McCarthy tells the stories of Forest Service leaders in the decades following the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act, which created new restrictions on motorized tools, commercial activity, and permanent structures. While the Act was clear in its goal of preserving areas in “pristine” condition, it left plenty of questions on how its implementation would look on the ground. How would crews work without power tools? Could legacy outfitters still guide paid trips in the wilderness? How would they manage wildland fire?

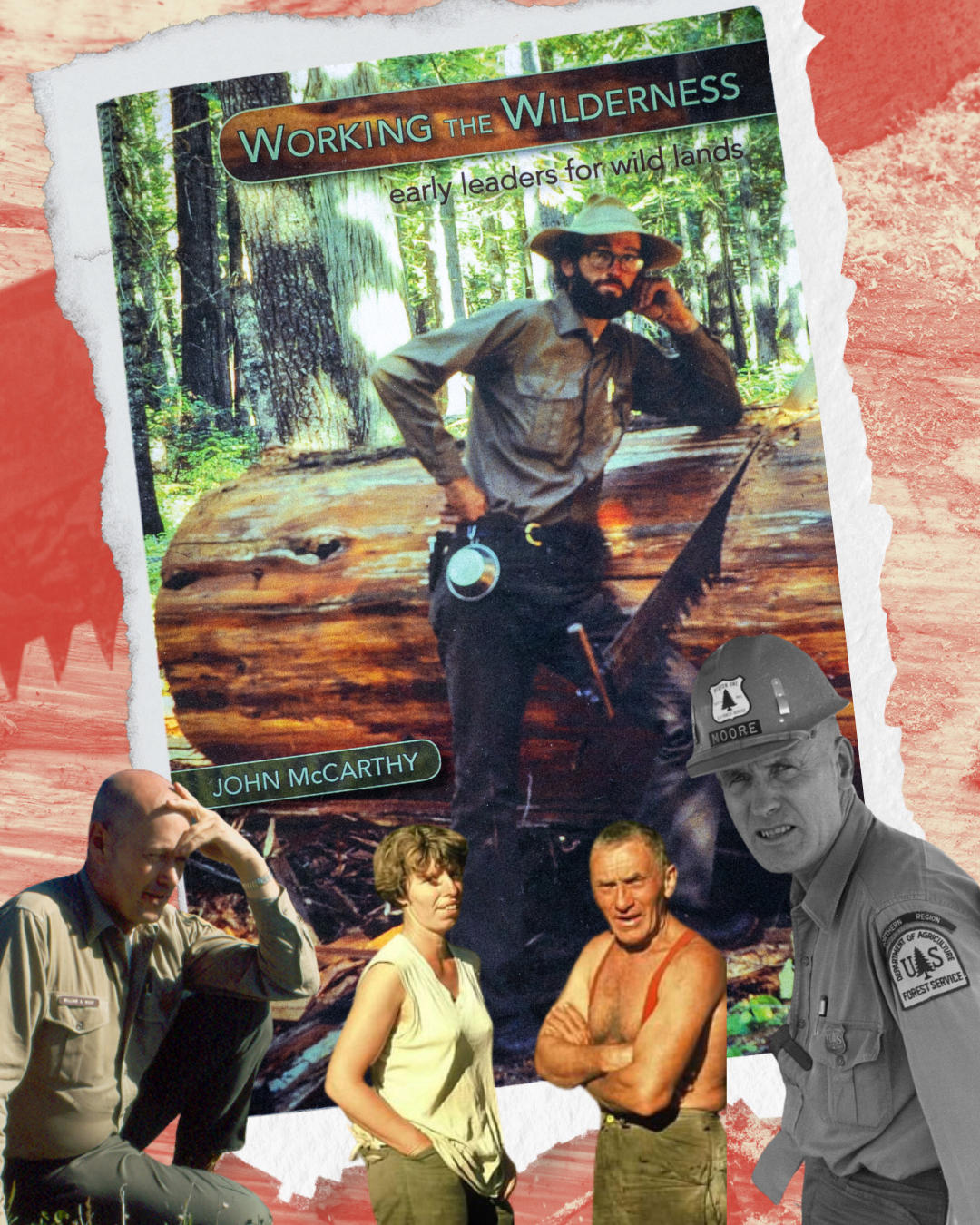

A journalist and former member of the Selway-Bitterroot trail crew, McCarthy spent years interviewing and working alongside the folks who grappled with these questions. They include: Emil Keck, a cantankerous but capable ranger; Penny Keck, a hardened trail worker and Emil’s wife; Bud Moore, a fur trapper who ascended to the highest ranks of the Forest Service and challenged the paradigm of wildfire management; William Worf, creator of the first wilderness management plans; and Warren Miller, expert crosscut saw filer.

Bud Moore, 1973. Photo by Janet Moore. Source: Montana History Portal.

These folks are individually fascinating. But taken together, we can see threads in the bigger story of what it’s like to be a land steward for the federal government. Those of us who have worked in public lands can relate to the mentor who is highly skilled, extremely dedicated, and perhaps a bit intimidating. And like many folks working in land management today, these early leaders had, at times, strained—even combative—relationships with the agencies that employed them.

Emil and Penny Keck worked constantly, logging countless hours of unpaid overtime building bridges, clearing trails, and assisting on wildfires. But they also rankled their superiors by ignoring paperwork and standard operating procedures, and were eventually forced out of the wilderness cabin they had lived in for years.

Bud Moore was a traditionalist mountain man who challenged his agency’s approach to wildfire, which for decades operated on a mandate to “suppress all fires.” Moore believed, correctly, that low-intensity burns were part of a healthy forest ecosystem, and pushed the Forest Service to allow remote wilderness fires to burn, monitored but uncontrolled.

William Worf grew up in a ranching family, raised on the homesteader’s philosophy that land was something to be used. But Worf would later become a stalwart defender of wilderness, helping to develop the original guidelines of implementing the Wilderness Act. After his 30+ year Forest Service career, he co-founded the nonprofit Wilderness Watch and filed lawsuits against his former employer when the agency failed to uphold wilderness regulations.

Without seeking official approval from the Forest Service, Warren Miller learned everything he could about crosscut saws and became one of the best crosscut filers in the world. He later published several agency documents on crosscut saw use and care. He, too, ultimately retired from the agency after several spats with a supervisor.

Penny and Emil Keck, 1970s. Photo by Alan C, Moose Creek Ranger District. Source.

These individuals were imperfect (all have died, save Penny Keck). They were products of their own times with their own blinders. They are all, conspicuously, white. They didn’t always agree with one another. As leader of Wilderness Watch, Worf’s preoccupation with “pristine” wilderness led to friction with the Idaho Conservation League about new wilderness designations. Emil Keck didn’t believe women could do trail work until Penny convinced him otherwise. Emil also saw himself as exceptional, once saying, “It’s the Forest Service responsibility to manage the god-damned land and it’s the public’s responsibility to shut up.”

Behind all the surliness was an extreme dedication to land stewardship. They were good at their jobs not in spite of their grit, but because of it. When the Kecks or Warren Miller encountered hunting guides flouting wilderness rules, they confronted them and held them accountable. They led crews working in grueling conditions, never asking crew members to do anything that they wouldn’t do themselves. When government money fell short, they paid out of their own pockets. Visitors, outfitters, and crew members observed their grizzled dedication and showed respect, even when disagreements flared up.

Warren Miller, crosscut saw filer. USFS Photo.

Today, “bureaucrat” has become synonymous with all government employees. The Kecks didn’t see themselves as bureaucrats, and the public didn’t see them that way, either. These people were paragons of self-sufficiency, themselves exasperated by the demands of bureaucracy. The Kecks cared more about building bridges than they did about overtime pay. They ignored paperwork to have more time clearing trails for hikers. Warren Miller didn’t ask for his job title to be “crosscut saw filer.” He just started doing it. They didn’t serve their supervisors or the paperwork or even the Forest Service; they served the public and the land.

William Worf. Photo by Bud Moore. Photo source: Montana History Portal.

As I write this, the future of our land managing agencies is uncertain. Many conservation workers feel burned by the government, betrayed by their own agencies who are failing to protect them and the land they steward against a hostile administration. In conservation, losing your job means so much more than losing a paycheck. It means losing your connection to a place: a beloved trail you maintained, a shed where you sharpened tools, a nursery where you raised seedlings. People who do this work care. Those who don’t, don’t last very long.

Working the Wilderness is more than Idaho history—it’s a story about people who give a damn. Emil Keck was singular, but not peerless. There are many dedicated and formidable people in conservation, working countless hours of unpaid overtime and risking life and limb. Most of them labor quietly and happily in the lonely wilds, and we are lucky to have them. Working the Wilderness teaches us that the best stewards are those who put the land first, and who, when faced with misguided supervision, know when to follow their hearts.